A neighborhood alley in Bethesda

"Public art is a reflection of how we see the world – the artist's response to our time and place combined with our own sense of who we are."

-Public Art in Philadelphia by Penny Balkin Bach.

What is Public Art

According to Americans for the Arts (Public Art 101), public art can be considered as an art in public space and is accessible by the public. We often associate images of a historic bronze statue or giant sculpture in a park as public art. Yet, public art can take a wide range of forms, sizes, and scales. It can also be temporary or permanent.

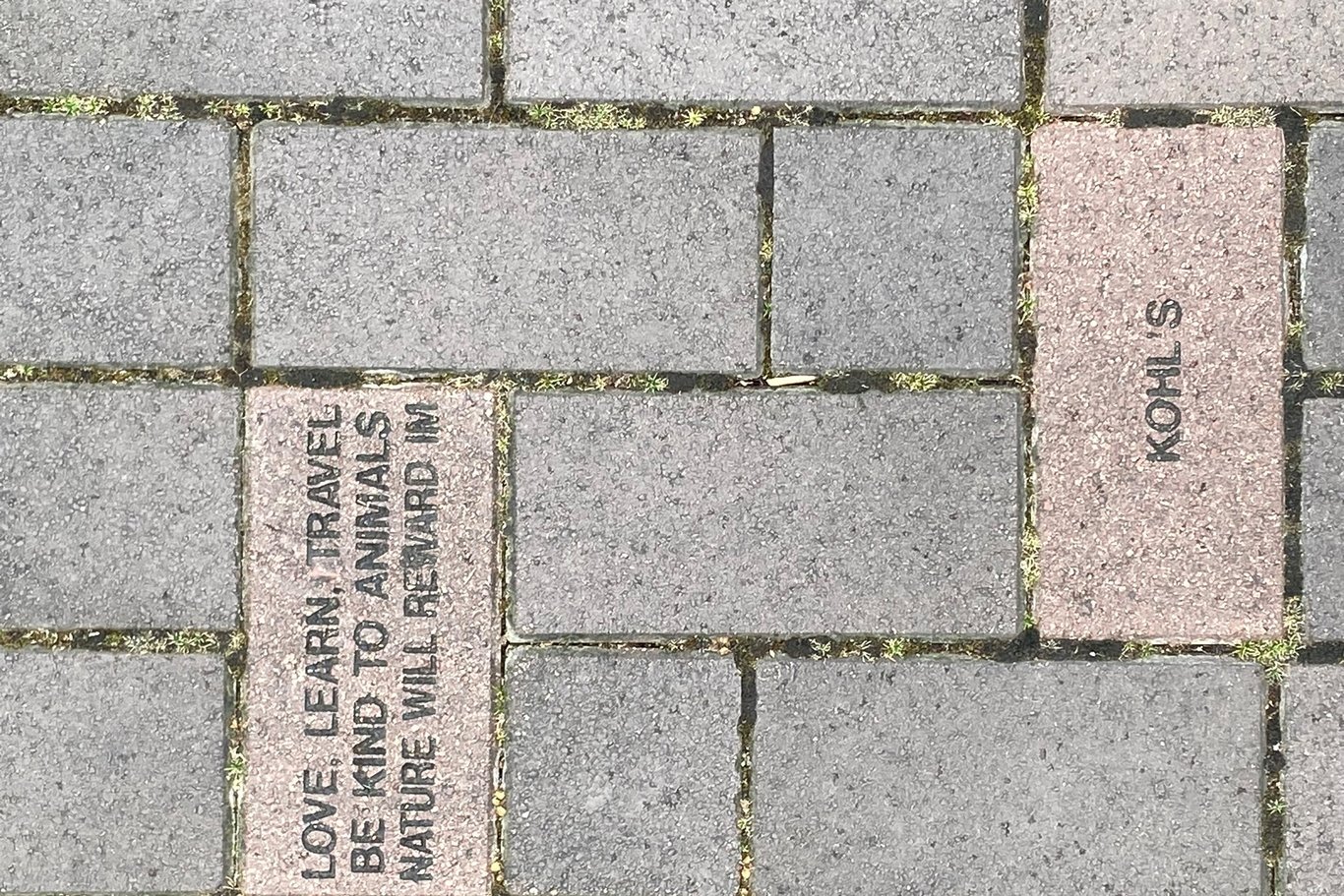

Penny Balkin Bach, the executive director of the Association for Public Art, further explained that public art could be fifty feet high or call attention to the paving beneath your feet. What distinguishes public art is the unique association of how it is made, where it is, and what it means.

Public art can call attention to the paving beneath your feet

Public art can be several stories tall.

Why Public Art Matters

It matters if you are a developer

In 1974, the artwork in Montgomery County became an amenity requirement to be provided by developers in exchange for a higher density under optional method development. Under this zoning procedure, land assembly and mixed-use development are encouraged through various public amenities and facilities, such as open space, affordable housing, farmland protection, environment conservation, etc.

This ordinance was designed for a dense downtown area, for example, Central Business District (CBD) or mixed-used zone, for instance, Commercial Residential (CR). Its intention of including public art as an amenity is to create a more attractive urban environment. Developers can also pay a fee of 0.5% of the project cost if they decide not to include public art in their development scope.

Bear with me here. There are three stories I found interesting to share.

It matters if you are a place-lover

Haas&Hahn and their mass painting project

Jeroen Koolhaas and Dre Urhahn are two artists from Netherland. In 2007 they came to a village in the north of Rio, Brazil, and decided to test an idea of painting a slum. They started with a single mural painting (of three houses) - "Boy with the kite" (2007), then a second project with a giant retaining wall at the hill- "Rio Cruzeiro" (2008). In 2010, with the local community's help, they painted murals over 7,000 square meters (75,000 square feet) of the public square in the Santa Marta. The series of mural paintings is known as the "Favela Painting Project," which was accomplished by twenty-five local people from the neighborhood. Since this Favela project, the slum has turned into a place of shared pride.

In 2011, Koolhaas and Urhahn chose to live just a block off Germantown Ave in the north of Philadelphia to begin their 16-months commercial corridor beautification project-also known as Philly Painting. They started with hosting BBQs in the community, came out of 35 combinations of native color pallets, and hired local people to accomplish the project. In the end, they got permission to paint 51 buildings and storefronts along this corridor.

Jose Miguel Sokoloff and his Christmas lights

Before FARC signed a ceasefire accord with the president of Colombia in 2017, guerilla was always the social issue in Colombia. In 2010, Sokoloff received a mission to persuade FARC guerrillas to demobilize. Since then, his agency had placed nine decorated holiday trees in the jungle and floated a raft of glowing plastic balls, filled with gifts and messages from family, down to the river that guerillas typically traveled. Later in their last campaign, the agency lit up wayfinding "stars" over local villages, offering lost insurgents a way back.

At the end of this project, 17,000 former guerrillas were demobilized and returned to their hometown.

Antanas Mockus and his much bigger classroom

Mockus, a mathematician, a philosopher, also a Mayor of Bogota (1995-1997 and 2001-2003), once hired 400 plus mimes to control traffic at chaotic and dangerous streets in Bogota. He sent mime artists to make fun of rude drivers and jay-walk pedestrians. This mayor handed out a stack of red cards so people could call out antisocial behavior rather than punching or shooting each other. He also made other theatrical moves, such as appearing on TV programs, taking a shower, and turning off the water as he soaped during a water shortage.

His motto is "Knowledge empowers people." He thinks that once people know the rules and are exposed to art, humor, and creativity, they are much more likely to accept the change.

An Art? Or Not an Art?

You might be wondering why I put the stories here. These stories are outdated, and most of them are not in the United States.

Well. It has to do with our definition of "art" and why we place the "art" in our public space.

As mentioned above, public art has many forms-from as small as engraved paver to as large as several feet of sculpture. Cities also vary in their criteria for what constitutes "art." For example, in Montgomery County, "work of art" is defined as "an object, objects or surface embellishment produced with skill and taste." (County Code Chapter 8 Building, Article VI section 8-43). In other words, we have this preconceived notion that "public art" must be physical and tangible.

However, if you search for the mission and vision of having public art, you will read as follows:

Inspire communities through placemaking

Nurture artists engaged in public art

Promote cultural enrichment

Engage diverse communities through projects and dialogue

Foster emerging and established local artists.

That being said, if we only focus on making "art" accessible to the public and on accomplishing these visions, we are limiting our "public art" to a particular "object" format. Hence, we need to see "public art" from a slightly different angle. Many of the arts consist of these five broad categories:

Performing arts (music, dance, theater, singing, and film.)

Visual Art (crafts, design, painting, photography, sculpture, and textile.)

Literature.

Culture.

Online digital and electronic arts.

Hiring mime artists, for example, to standby certain places that people litter the most could engage communities and stimulate dialogue. (Mime is also a form of performing art). A place like parks with picnic facilities, a busy farmers market, a summer outdoor movie venue, or a shopping strip could also be a public environment for experiencing art.

Throwing a book reciting event or placing a mini-library stand could also promote cultural enrichment and improve the quality of life. Flying lanterns that symbolize hope, or hand out prayer candles could foster community identity and spirit.

Maximize the impact of $100,000

A fee to the trade-off by not installing the artwork with a cap of up to $100,000. To translate this game rule: unless the project's construction cost is less than 20 million, in that case, the developer will pay less than $100,000. Otherwise, $100,000 is the must-spent fee for a density-driven project.

However, most of the developments driven by the incentivized density are located in a wealthier neighborhood. Imagine a typical five-over-ones apartment with about 150 units would cost more than 25 million dollars on a national average (1). High-rise concrete structure with similar number of units will cost even more than 40 million dollars on a national standard. Not to mention the project locates in a more affluent downtown area.

Most of well-developed neighborhoods have already had a quality of life. Having a piece of artwork only adds extra decoration to the community, not necessarily to foster community identity, its spirit, nor encourages a dialogue.

Having a piece of artwork only adds extra decoration to the community, not necessarily fosters community identity and spirit, nor encourages a dialogue. What if we can make public art like this? Scroll through image below. (Background image via google.com)

Take a look at how the Philly project spent their fund and the cost of other art activities; you will realize this $100,000 can:

Paint, plaster (or beautify) 8-10 shuttered buildings in the nearby neighborhood.

Hire two mimes for 200 hours and not worry about artwork's annual maintenance and cleaning fee. (Source: national pricing for mimes in the U.S. )

Hang 96,000 feet (18 miles) of the outdoor LED light string with a total of 48,000 lightbulbs. If each light bulb consumes 10 watts per hour, it will only cost 1,920 kilowatt-hours per night (from 9 pm to 1 am).

What's the takeaway?

Please don't mistake this as a denounce for large, expensive artworks prohibited from our communities. There are towns or cities were built around works of art. These places have visitors all over the world to see their unique culture in a midst of artworks. But at the same time, we need to be mindful of our genuine intent and true purpose of having public art in our community. The only way to foster a community's spirit, encourage dialogue, enrich local culture (sometimes manage local problems), and nurture local artists is by bursting many creative minds and collaborating with many similar but diverse people to realize a particular vision. A mayor, a developer, a foreigner, or neighbor Joe can all conduct or be involved in a "public art" movement.

Notes and references:

National average cost of a mid-rise building is about $175-$250 per square feet. Using $200 per square feet as a baseline, a construction cost for a project of 150 units with average unit size of 850 square feet will be 25.5 million. High-rise building is about $225-$400 per square feet. Taking $300 per square feet as a benchmark, a construction cost for the same program listed above will cost 38.5 million.

“How painting can transform communities“, TED Global 2014

“How Christmas lights helped guerrillas put down their guns“, TED Global 2014

Mara Cristina Caballero. (2004, March 11). “Academic Turns City into a Social Experiment”. The Harvard Gazette.

“Why does public art cost so much”, Caitlind R.C.Brown & Wayne Garrett

“Montgomery County Public Art Guidelines”, (2018, September)